Shany Dvora

Shany is a Tel Aviv-based graphic designer, typographer, and artist. Find her on Instagram and on her personal website.2021 saw rising hostility against queer identities in Turkey, bringing the topic to the fore in discussions about its fraught language politics. By uncovering a largely undocumented Ladino vocabulary, Altaras sheds light on historical gender politics in Sephardic Turkey, and offers a means of building toward a Ladino without lexical limits.

A dinner commemorating the life of Yadid’s grandmother prompts a series of reflections about the enduring vivacity of her spirit and the power of food as a tool for active remembrance.

The history of the seipa, a sword-shaped protective amulet worn by Kurdish Jews, can help us better understand how to care for one another and build trust across communal divisions in the face of illness and collective hardship.

The Turkish writer Moris Farhi was an embodiment of a regional pluralism that the Republic would seek to cover under the blanket of nationalism. His faults as a starry-eyed representative of Turkish-Jewish unity expose the potency of the Jewish voice, and its silence, in Turkey.

The daughter of immigrants from Mashhad’s crypto-Jewish community, Amini recounts her endeavor to move into the student dorms at Barnard College amid a retaliatory hunger strike at home and antiwar protests on campus.

Banafsheha digitally manipulates a series of photos sent to her by her grandmother, toying with physical and impalpable notions of preservation in a tenderly awkward fight against time.

Discussing such topics as the intersection between Mizrahiut and post-Soviet anthropology, trans experience, cinema, and Latin American migration, the works included in our Winter 2021 release examine facets of Middle-Eastern Jewish life previously undiscussed at ZAMAN. We are grateful to have the engagement of readers and contributors across the world who push our publication toward a place of greater breadth and dimension with each issue.

As Israel ramped up rhetoric against the Egyptians in the late 1960s and early 1970s, families of all backgrounds and all walks of life gathered together in their homes to laugh, smile, and cry, watching the films of the “enemy.” By 1973, the two nations again found themselves at war, and yet the movies still captivated the Israeli public. In the morning, Israeli sons were sent to war on Egypt’s border, and in the evening their parents watched Egyptian films.

The Persian word for heart is ‘qalb’. When you talk about the throbbing, blood-pumping organ in the middle of your chest, ‘qalb’ is the word you use. But when it comes to what English-speakers know as matters of the heart, in Persian, they sit squarely in the del. When you're forlorn and missing someone, you're deltang — your del feels tight, not your qalb. When you sympathize with someone's misfortune, you're delsooz — your del burns for them. When you're overflowing with emotions and need to unload them, your del is por, or full. And the friend who listens supportively as you unload your woes is your deldar — they have your del.

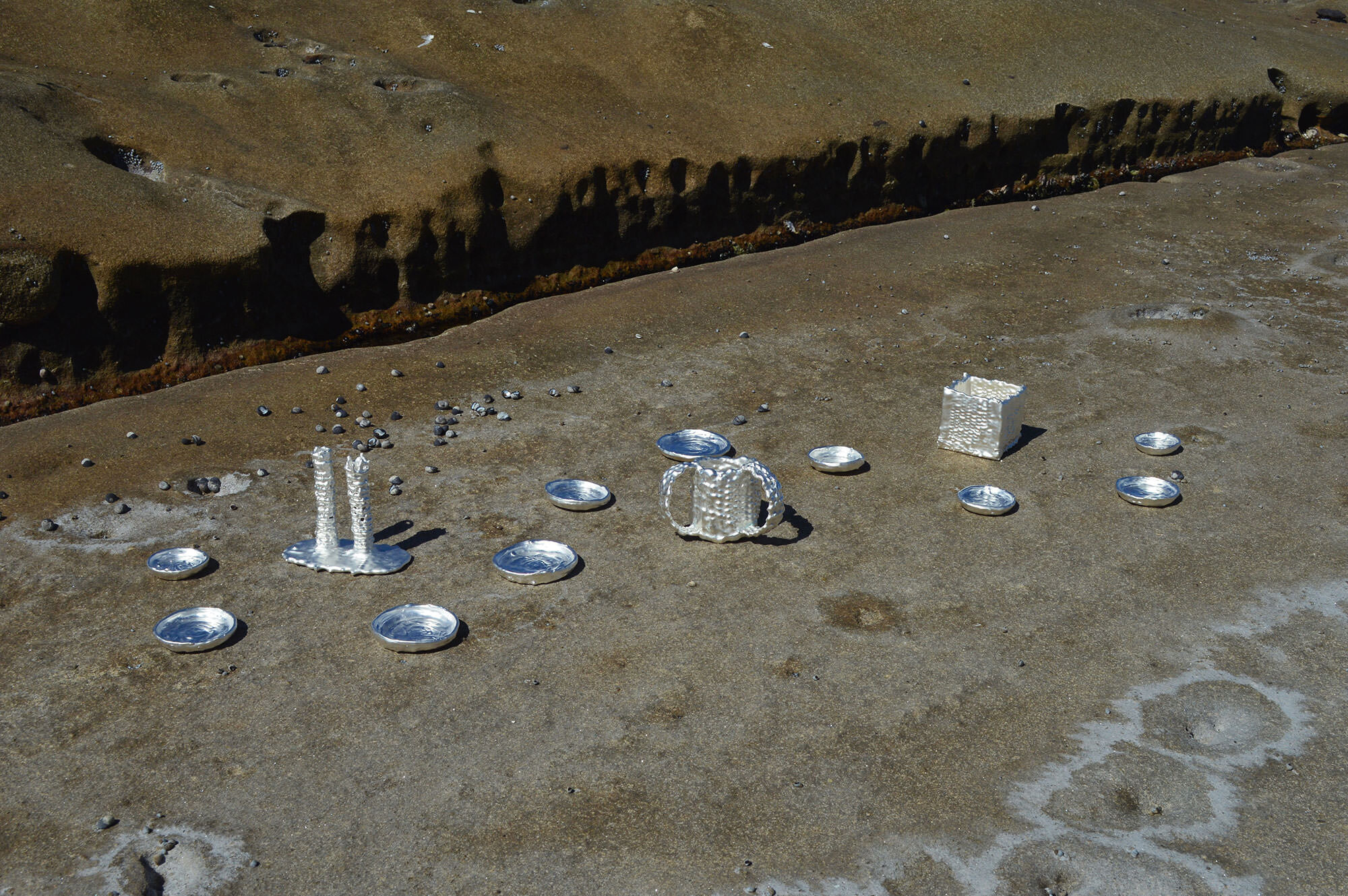

ZAMAN Co-Editor Sophie Levy speaks with Mika about the title of their Judaica project, its connection to the concept of "Jewish temporality," practicing Jewish ritual as a trans person, and the value of participatory, inviting design.

Misha shifts his weight from one foot to another. He holds his gaze firmly locked, and then sighs. He continues that his mother often recounted how “the camps were a reminder that all people can help each other out. Azeris, Estonians, Russians, Tatars – they were all in the camps alongside us – they shared their food with us, and we shared ours with them.” He says, “they joined Jewish celebrations, and my parents joined theirs.”

Editors Evan Mateen and Sophie Levy met with Dr. Sternfeld over Zoom to discuss the ripple effects of the publication of his book Between Iran and Zion, the implications of studying Iranian Jewry as an Israeli scholar in the US, and the future of Middle-Eastern Jewish history as a discipline.

This series of artworks was influenced by my family’s history, which unfolds between the Ottoman Empire, the Spanish Empire, and the Republic of Brazil. My mother’s side of the family settled in Brazil after fleeing the Spanish Inquisition as marranos – Sephardim who moved through public society as Christians, yet secretly practiced Judaism in the privacy of their homes. My father’s side of the family came from Ottoman Syria in the wake of the Assyrian Genocide, and from Egypt after WWI.

I left my / Jewishness / for shame of / a broken story. / I return to these / details to understand / what was lost. / How we lost / our pathway back / through the hills / past an old border. / New borders / of mind / preventing / return.

Based on the siddur of Saadia Gaon, Persian liturgy developed over hundreds of years into a distinct rite entirely separate from those of Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Yemenite Jews. Persian Jews generally sat on the floor, removed their shoes in synagogues, and likely regularly engaged in full prostration. But genizah manuscripts reveal fascinating variations in language and Persian Jewish tradition that suggest our forgotten heritage is a unique one among modern Jewish communities.

The lives of Mashhadi Jews had been a mystery since the day they were forcibly converted to Islam, a day often referred to as Allahdad, or God’s Justice. These newly converted Muslims were called jadid al-Islam and could be seen observing Ramadan and buying halal meat from the city’s markets. Little did the surrounding Shia Muslim community know what lengths the Mashhadi Jews went to preserve their Jewish faith and identity behind closed doors.

Cohen’s book focuses on the fundamental question: What defines Jewish peoplehood/personhood, if, at different places and points in time, it couldn’t so clearly be defined in resistance to an “other?”

It's rare for English-speaking audiences to find prosaic accounts and imaginations of Mizrahi life written by an Israeli author that were originally composed in English, rather than translated from Hebrew. Ayelet Tsabari's work offers us a glimpse into her life as a Yemeni woman born in Israel not only by way of content- but by way of language; Hebrew makes itself subliminally known in her writing.

Jerusalem is a city of springs; hidden within her is a myriad of metaphorical aquifers, each one spouting the words of dozens of prophets over the years. They are countless in number, but two are of particular cultural and culinary importance to me: Mahane Yehuda and the Arab Market near the Damascus Gate in the Old City—what Palestinians usually call Musrara Market.

A younger generation of Jews in Turkey, fed up with suppression and silence, has come together to create an online news and opinion platform: Avlaremoz (let’s talk).

A series of embroidery works depicting bodies, some whole and some fragmented. They are surrounded by a hand-woven pattern, recalling the shapes, colors and processes of traditionally woven textiles in a small, intimate format. The bodies are androgynous, comfortably and vulnerably in a state of in-between-ness, inviting a gaze to view them as they are.

A deconstruction of Ashkenormativity is necessary, but certainly not enough to urgently address the ways in which the privileges of Jewish people, however conditional they may be, can make us complicit in systems of white supremacy.

The Palestinian Jewish author celebrated an “exotic” hybrid of Arab and Jewish identity not in order to shift Zionism’s Orientalist premises or to intervene in the political tensions brewing because of it; Rather, Shami’s work was a protocol for racialization, and a significant contribution to Zionist settler-ideology, in its appropriation of Arabism.

Glimmers of violence, hope, brotherhood, and belonging grace this poem by Gabie Yacobi about her father's coming of age between Iran, Israel, and California.

Our editors talk with Galeet about her family’s ties to Iranian and Jewish music, her multifaceted approach to her work as both a scholar and a performer, and her thoughts on the future of music in American Jewish congregations.

For many Mizrahim, navigating our place in discussions about the Holocaust is a complicated task. How does my position relative to it as a Persian Jew guide my presence in conversations with other Jewish people? How do the obligations attached to my identity shift when I leave those spaces? And what has a new understanding of my family history taught me about Jewishness?

We are in a global moment of reckoning that is asking us to re-examine how our identities are not static or monolithic traits, but situationally-adaptable variables informed by our positions in larger social, political, economic, and cultural realities. Our understanding of identity today is ever-changing, constantly being shaped and defined by the roles we play across different communities.

Ruben Shimonov’s hybrid identity as a Bukharian, Sephardic, and Mizrahi Jew continuously informs his work as a community builder, educator, and artist.

In Shany Dvora’s graphic works, dark eyes and placid faces peer out from behind languid, spliced calligraphic forms. They exude a sense of determination to continue to see and be seen, to continue to speak and be spoken.